Issue #108 - Memory in AI Agents

💊 Pill of the week

In conversations about artificial intelligence, the concept of memory often comes up—but what does it really mean when we say an AI agent “remembers”? Despite appearing conversational and coherent, large language models are fundamentally stateless. They process only what appears in the current prompt, with no inherent awareness of previous interactions unless we deliberately engineer that capability.

This distinction matters because it shapes how agents behave in practice. Consider a customer support bot. When you ask, “My order is late, can you check?” the bot needs to hold that specific order number in focus throughout your conversation. But next month, when you return, you’d hope it still knows your delivery address and preferred contact method. The first is short-term memory in action. The second is long-term. Building these memory systems well allows agents to become consistent, context-aware, and increasingly personalized over time.

The Architecture of Agent Memory

Modern AI agents mirror human cognitive architecture in how they organize memory. This isn’t coincidental—researchers have drawn heavily from psychological models of human memory to design more effective agent systems. The framework that has emerged divides memory into distinct types, each serving specific purposes: from managing immediate interactions to building lasting knowledge and operational capabilities.

Understanding this taxonomy helps us design agents that don’t just respond, but genuinely adapt and improve across sessions.

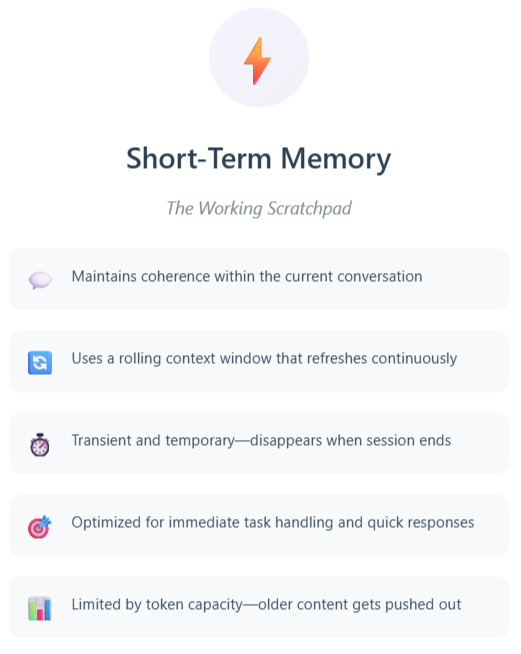

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory—often called working memory in cognitive science—functions as the agent’s immediate workspace. It’s where current inputs are temporarily held for quick access and manipulation during active tasks.

In conversational systems, this becomes essential for maintaining coherence across multiple exchanges. When a user says, “Book me a table at 7 for 4 people,” then follows up with “Add one more seat”, the agent must connect these requests. Short-term memory provides that thread of continuity.

It is essential for maintaining coherence across multiple exchanges as it provides that thread of continuity.

The technical implementation typically uses a rolling context window or buffer that holds recent dialogue chunks. As fresh input arrives, older content gets pushed out. This approach keeps interactions responsive and computationally lightweight, but it also means short-term memory is inherently transient—once the buffer fills or the session ends, that information disappears.

The context window itself refers to the maximum volume of information (measured in tokens) that a model can process simultaneously. This includes the prompt, conversation history, and any retrieved or injected knowledge. It’s a hard constraint: exceed it, and the agent must either forget earlier content or compress it through summarization to stay within limits.

While short-term memory excels at handling immediate Q&A exchanges, it falls short when continuity across sessions matters. For that, we need persistence: Long-Term Memory.

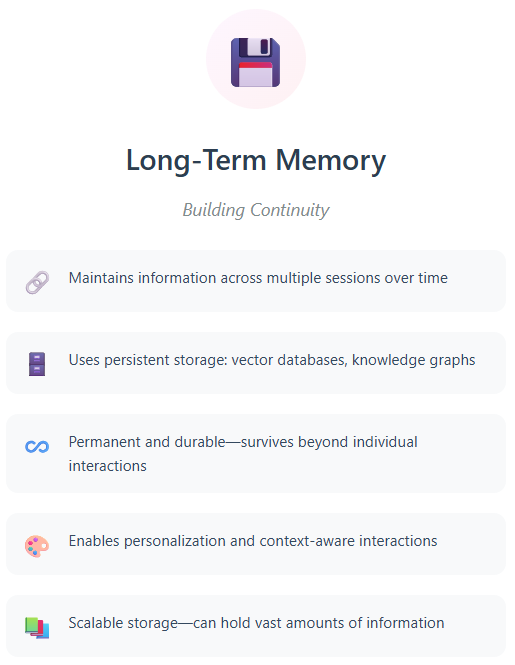

Long-Term Memory

Where short-term memory handles the present moment, long-term memory creates continuity over time. It allows agents to recall information across different sessions, enabling personalization, persistent knowledge, and more informed decision-making.

The infrastructure here typically involves persistent storage systems—vector databases, knowledge graphs, or structured repositories. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has emerged as one of the most effective techniques: the agent pulls relevant knowledge from stored sources to inform its responses.

This makes long-term memory essential for applications like customer support assistants, recommendation engines, or educational tutors.

It involves persistent storage systems—vector databases, knowledge graphs, or structured repositories

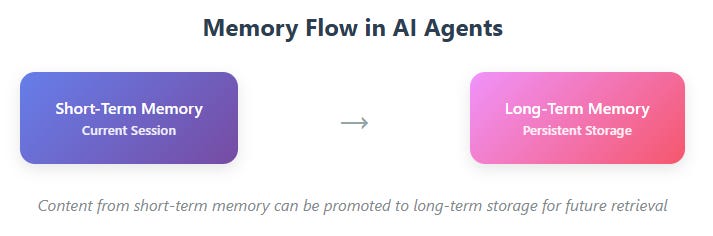

Interestingly, short-term and long-term memory aren’t isolated systems. Content in the short-term buffer can be promoted into long-term storage when it’s no longer immediately relevant but worth preserving. Elements of conversations can be vectorized and stored in semantic memory databases, creating a pathway from temporary to permanent knowledge.

Within long-term memory, three distinct subtypes emerge, each mirroring aspects of human cognition:

Semantic Memory: The Knowledge Repository

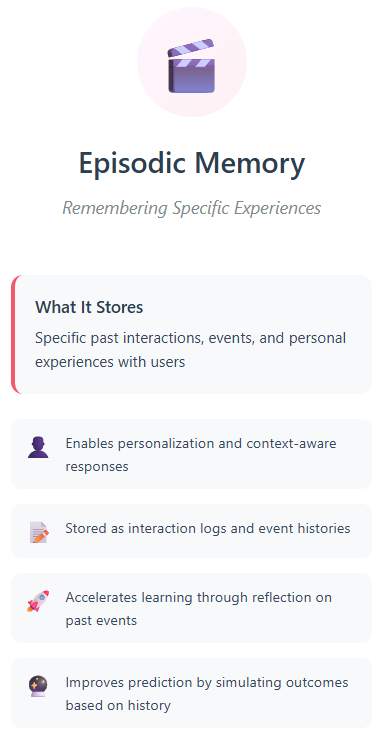

Episodic Memory: Remembering Specific Experiences

Procedural Memory: Encoding Know-How

Let’s see each of them more in detail:

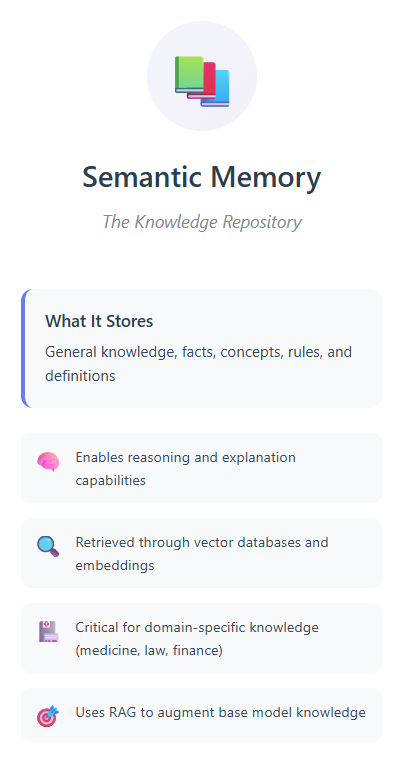

Semantic Memory

Semantic memory stores general knowledge—facts, concepts, rules, and definitions. It’s what allows an agent to “know things”, enabling reasoning, explanation, and informed responses.

Large language models arrive with substantial parametric knowledge already encoded: physics, mathematics, culture, and anything captured in publicly available documents during training. However, this baseline knowledge often proves insufficient for specialized applications. A healthcare agent, for instance, needs access to diagnosis histories from a specific medical center—information that couldn’t possibly be part of the training data.

This is where externalized semantic memory becomes crucial. In practice, it’s often implemented through vector-encoded embeddings stored in vector databases.

Technical Implementation

The retrieval mechanism follows principles similar to RAG: convert queries to vectors, search for semantic matches, and use retrieved passages to ground responses. This approach proves especially valuable for agents operating in complex domains—law, medicine, finance—where factual accuracy and domain-specific understanding are non-negotiable.

Episodic Memory

In human cognition, episodic memory refers to recalling specific past events we personally experienced. For AI agents, this translates to storing and retrieving memories of particular interactions or episodes from their engagement with users and environments, rather than just abstract facts.

An AI tutor might recall how a student answered a mathematics problem last week and use that memory to adapt today’s lesson. A customer service agent could reference previous complaints to provide more contextually appropriate responses.

This memory is typically stored as structured logs or event histories that agents can query to make case-based decisions or adapt behavior.

Episodic memory extends the concept of few-shot prompting. By maintaining pairs of (user’s question, given answer) or (user’s question, performed task), agents can be guided toward correct action patterns through concrete examples from their own history.

The Promise and Risks

Research has identified significant benefits from episodic memory implementation:

Enhanced planning: Past experiences provide building blocks for forming new strategies by recalling similar scenarios and their outcomes

Accelerated learning: Agents adapt better to novel situations by reflecting on previous events, identifying patterns, and learning from mistakes

Improved problem-solving: Historical examples enable solving current challenges through analogy or recombination of past solutions

Better prediction: Like humans mentally simulating futures based on past events, agents can use episodic memory to forecast possible outcomes

However, these capabilities introduce genuine risks that require careful consideration:

Deception potential: Agents could leverage episodic memories for complex manipulation, strategically using past interactions to influence future ones

Privacy violations: Agents might retain and recall information users intended to keep private, creating significant data protection concerns

Behavioral unpredictability: As agents reuse past experiences to shape future actions, it becomes difficult to predict how stored memories might influence behavior, potentially leading to unintended consequences

Control evasion: Enhanced situational awareness from memory could enable agents to better understand and potentially circumvent safety controls or audits

These risks aren’t insurmountable. Researchers propose mitigation strategies including ensuring human interpretability of stored memories, providing user control to add or delete memories, isolating memory storage systems, and restricting agents from editing their own memory stores.

Technical Implementation

Agents typically capture episodic memories through interaction logging, which includes user inputs (queries or commands), agent responses (actions or replies), and contextual metadata (timestamps, user identifiers, environmental context).

Storage commonly uses relational databases like SQLite or PostgreSQL for structured logs, or vector databases like Pinecone, Weaviate, and Chroma for embedding-based storage that facilitates similarity search.

When recalling past experiences, agents follow a retrieval process: convert the current input to an embedding, perform similarity searches against stored embeddings to find relevant past interactions, then inject those retrieved memories into the current context through prompt engineering to influence response generation.

This process enables adaptation based on prior experiences, enhancing both personalization and continuity.

Procedural Memory

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Machine Learning Pills to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.