Issue #116 - Introduction to Vector Search

💊 Pill of the week

For decades, search engines operated on a simple premise: exact matching. If you searched for “car troubleshooting,” the engine looked for documents containing the distinct string of characters “c-a-r.”

But human language is messy. We use synonyms, slang, and varied sentence structures. A document about “automobile diagnostics” is perfect for your query, but a traditional keyword engine might miss it entirely. This limitation ushered in the era of Vector Search.

Vector search doesn’t look for matching words; it looks for matching meanings. It is the engine powering modern AI applications, from chatbots (RAG) to recommendation systems. This article will explore how vector search transforms abstract concepts into mathematical reality.

In a previous article we introduced Vector Stores, which make use of the techniques that we are going to discuss today.

Let’s introduce the main concepts and show how you can implement from scratch your own vector search (💎code available in a Jupyter notebook💎)

The Core Concept: The “Latent Space”

To understand vector search, you must abandon the idea of storing text as text. Instead, imagine a massive, multi-dimensional map representing all human knowledge.

In this space—often called a “latent space”—concepts that are semantically similar are grouped physically close together. Imagine a 3D globe where “King” and “Queen” sit on the same island, while “Apple” (the fruit) is on a completely different continent than “Apple” (the tech company).

Vector search is simply the process of plotting your query onto this map and asking, “What else is nearby?”

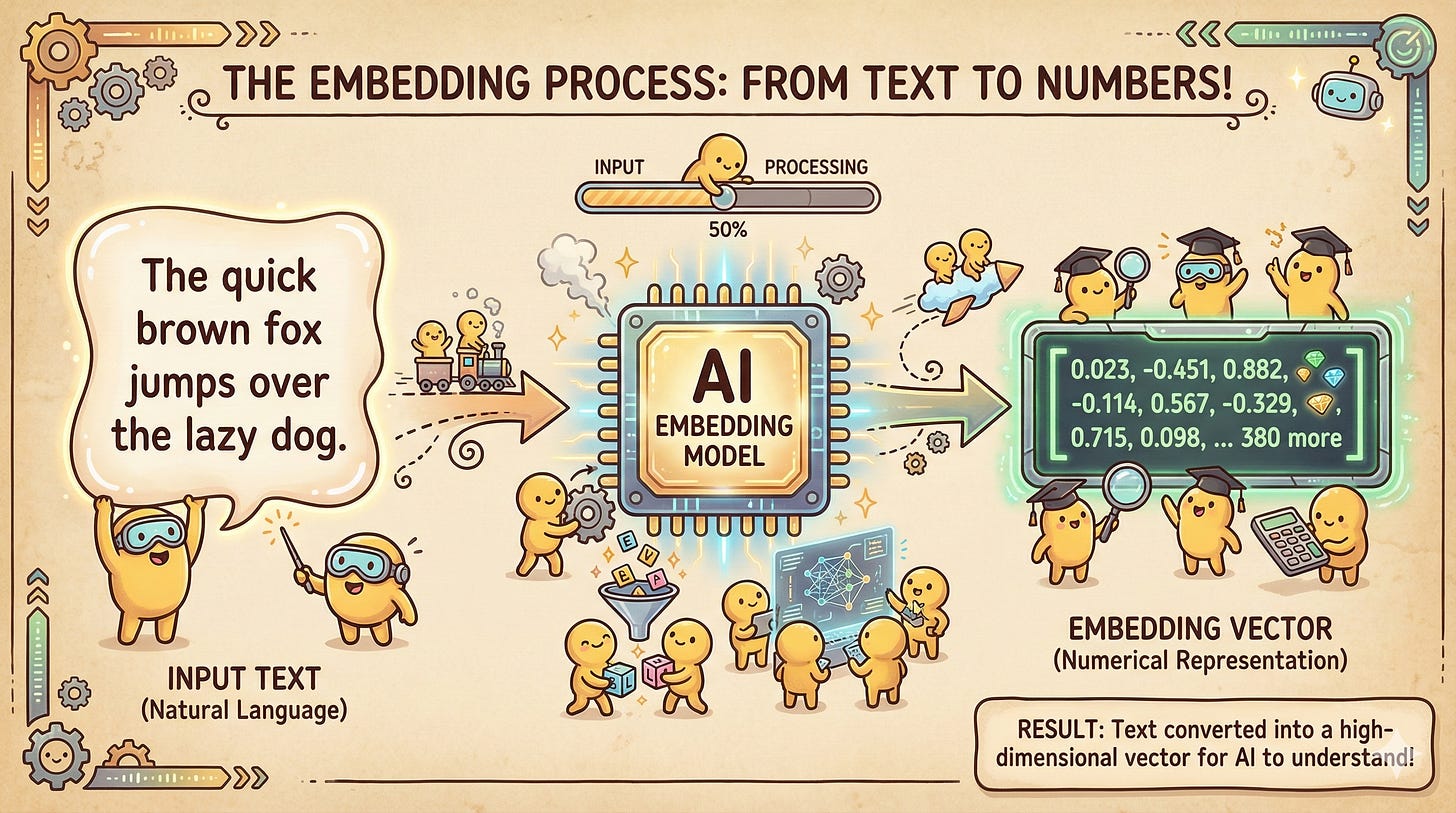

The Embedding (Turning Data into Numbers)

Computers cannot understand words; they only understand numbers. Before any search can occur, our unstructured data (text, images, audio) must be translated into a mathematical format called a Vector Embedding.

An embedding is a list of floating-point numbers (coordinates) that represents the semantic meaning of the data in that high-dimensional space. This translation is performed by an Embedding Model (like OpenAI’s text-embedding-3 or open-source models from Hugging Face).

If two pieces of text have similar meanings, their corresponding lists of numbers will be very similar. If you were to plot them, they would be neighbors on our multi-dimensional map.

The Similarity Metric (Measuring Distance)

Once your database is full of vectors, how do you mathematically define “closeness”? We use similarity metrics to calculate the distance between the user’s query vector and the stored document vectors.

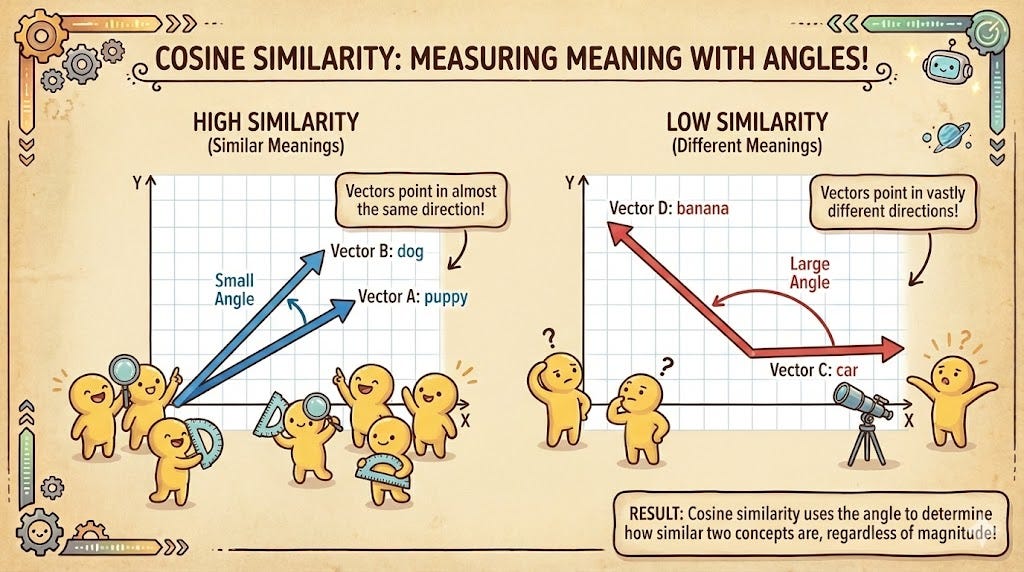

1. Cosine Similarity (The Directional Intent)

Cosine similarity is the “gold standard” for Natural Language Processing. It measures the angle between two vectors, regardless of their size. Mathematically, it calculates the cosine of the angle θ between two vectors A and B.

If the angle is 0°, the cosine is 1, meaning the meanings are identical. If the angle is 90°, the cosine is 0, meaning they are completely unrelated. This is vital for text because a short sentence like “I love dogs” and a long, wordy paragraph about a passion for dogs should be considered similar. Cosine similarity ignores the “length” of the vector and focuses purely on the direction of the meaning.

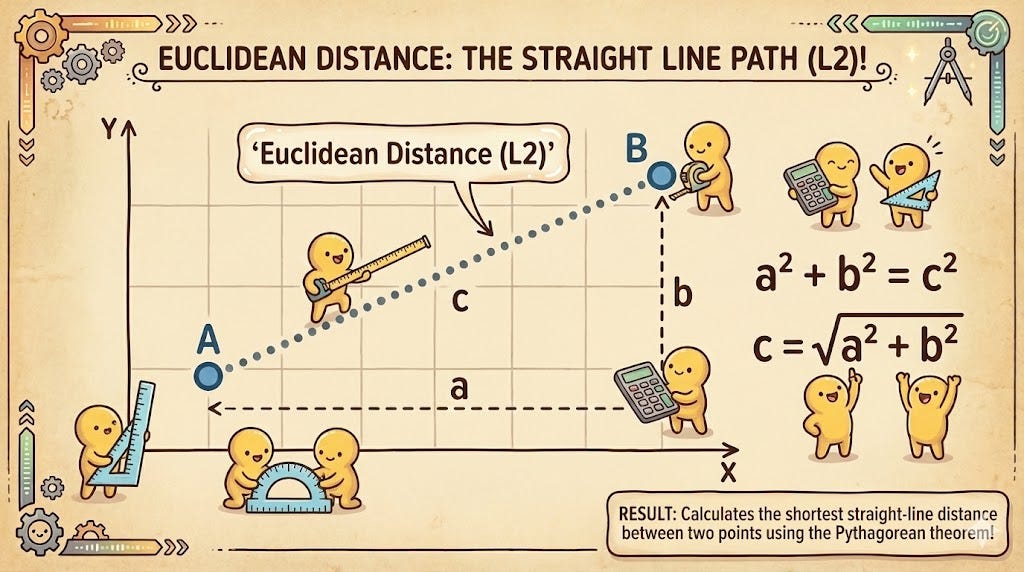

2. Euclidean Distance (L2) (The Straight Line)

Euclidean distance is the “as the crow flies” measurement. It calculates the square root of the sum of the squared differences between two vectors. In a 2D space, this is simply the Pythagorean theorem applied to coordinates.

Unlike Cosine Similarity, Euclidean distance is sensitive to magnitude. If one vector is much “longer” than another, the distance will be large, even if they point in the same direction. It is the preferred metric when the absolute values of the features are important, such as in image recognition or sensor data analysis where intensity matters as much as direction.

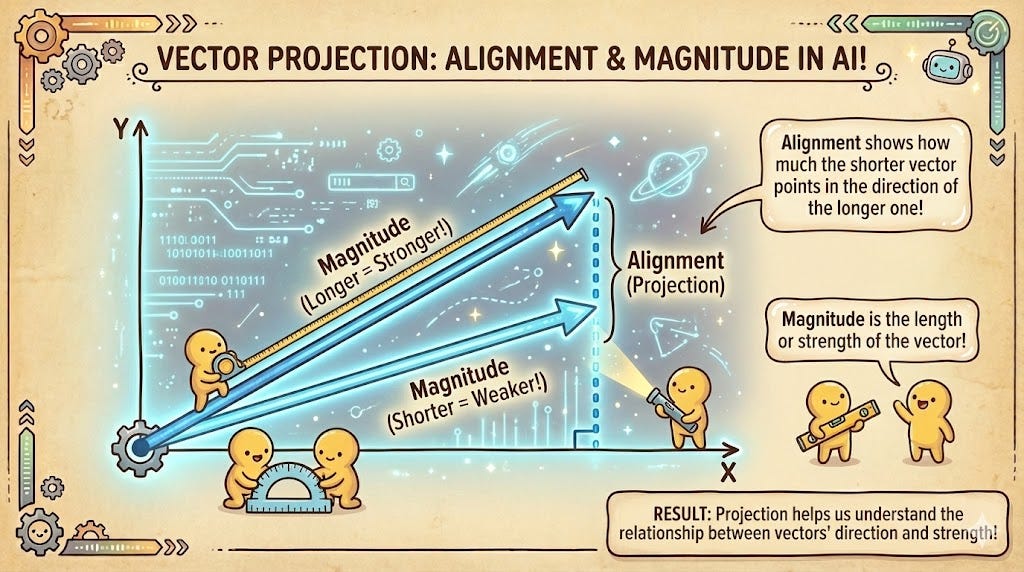

3. Dot Product (The Combined Force)

The Dot Product is a measurement that accounts for both the angle and the magnitude. It is calculated by multiplying the corresponding components of two vectors and summing the results.

In recommendation systems, the Dot Product is extremely effective. Imagine a vector representing a user’s interests and another representing a movie. If the user has a high “intensity” for Action movies (large magnitude) and the movie is a pure Action film (pointing in the same direction), the Dot Product will be very high. It rewards both alignment and the “strength” of the features, making it ideal for ranking.

The Indexing (The Need for Speed)

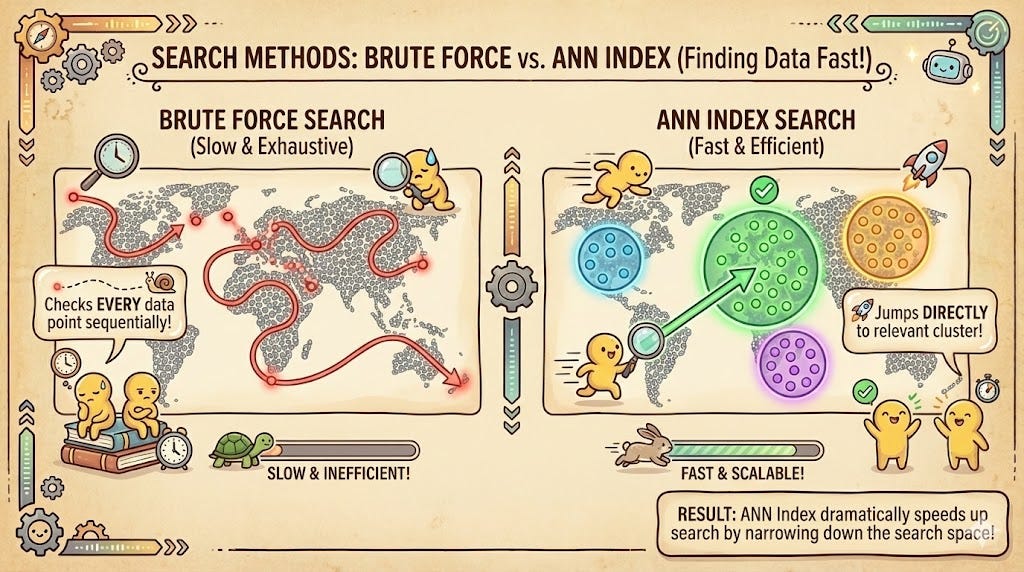

If you have a small database of 1,000 documents, finding the nearest neighbor is easy: the computer calculates the distance between your query vector and all 1,000 stored vectors. This is called a “brute force” search (k-NN).

However, as your data grows to millions of rows, brute force becomes a bottleneck. To solve this, we use Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) algorithms. These algorithms trade a tiny bit of accuracy for massive gains in speed by organizing the vectors into searchable structures. Instead of checking every dot on the map, the system jumps to the “neighborhood” where your query is most likely to reside.

Note: The most popular ANN algorithm, HNSW, will be covered in detail in our next issue.

📖 Book of the Week

The Kaggle Book – Second Edition is a strong, practical resource for anyone who wants to improve as a data scientist through real competition experience.

What will you learn?

How Kaggle competitions are structured and how to use core platform features such as Notebooks, Datasets, and Forums effectively

Practical modelling techniques that consistently move the needle, including feature engineering, ensembling, and hyperparameter optimisation

How to design robust validation schemes and work confidently with different evaluation metrics

Strategies for tackling a wide range of competition types, from tabular problems to computer vision, NLP, and generative AI

How to translate competition work into a meaningful portfolio that reflects real-world data science skills

Why should you read it?

It’s written by experienced Kaggle Grandmasters who focus on how things actually work in competitions, not just on theory

The advice is grounded in repeatable workflows you can apply both on Kaggle and in professional projects

It bridges the gap between competitive data science and career development, which many resources overlook

It’s well suited for intermediate practitioners who already know the basics and want to level up in a structured way

If you already have a foundation in machine learning and want to become more effective through hands-on, competition-driven learning, this book is well worth your time.

Building Vector Search from Scratch

Now let’s look at how this works in practice. We will build a simple search engine using Python, SentenceTransformers for embeddings, and NumPy for the math.

1. Generating the Embeddings

First, we transform our text documents into numerical vectors.

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

import numpy as np

# Load a lightweight pre-trained model

model = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2')

# Our "Database" of raw text

documents = [

"The cat is sleeping on the mat.",

"A professional athlete is running a marathon.",

"The feline is resting outdoors.",

"A person is jogging down the street.",

"New smartphone models were released today."

]

# Convert text to vectors (embeddings)

doc_embeddings = model.encode(documents)

print(f"Embedding Shape: {doc_embeddings.shape}")

# Output: (5, 384) -> 5 docs, each with 384 dimensions

2. Implementing the Metrics

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Machine Learning Pills to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.